Medical pluralism describes the availability of different medical approaches, treatments, and institutions that people can use while pursuing health: for example, combining biomedicine with so-called traditional medicine or alternative medicine. If we look closely at how people deal with illness, navigating between home remedies, evidence-based medicines, religious healing, and other alternatives, we can notice that some degree of medical pluralism is present in every contemporary society. As a concept, medical pluralism lies at the heart of the discipline of medical anthropology, which owes its birth to the study of non-Western medical traditions and their encounters with biomedicine. This entry describes the history of debates in the scholarship on medical pluralism, the search for an appropriate terminology, and current theoretical and methodological developments. In the 1960–1980s, many studies were focused on patients and their strategies of choosing a ‘medical system’ from a plurality of options. In the 1980–1990s, the notions of medical systems and medical traditions came under severe criticism for their inability to describe how medical thought and practice change over time, often being too eclectic to fit single systems or traditions. As a result, anthropologists began investigating patient-doctor negotiations of treatment, their diverse health ideologies, as well as the role of political-economic factors in shaping the hierarchies of medical practice. Additionally, scholars began examining the processes of state regulation and institutionalisation of medical traditions (for example, as ‘alternative and complementary medicine’ [CAM] in Europe and North America). This opened the field of medical anthropology to new debates, terminology, and geographical horizons that are trying to account for the pluralist nature of medicine in the twenty-first century. Transnational migration, the Internet, the rise of alternative medical industries, and the global flow of medical goods and knowledge all serve as catalysts for ever-more pluralistic health-seeking practices and ideologies.

Introduction

Medical pluralism describes the availability of different approaches, treatments, and institutions that people use to maintain health or treat illness. Most commonly, medical pluralism entails the use of Western medicine (or ‘biomedicine’) and what is variously termed as ‘traditional medicine’ and ‘alternative medicine’. For example, cancer patients might complement chemotherapy with acupuncture and religious healing; or women who want to get pregnant might combine hormonal treatment with home remedies and Yoga. Scholars of medical pluralism have used different terms such as traditional, indigenous, folk, local, or alternative medicine, but since they all imply distinction from biomedicine, this entry will refer to them as ‘nonbiomedical’ practices.

As a theoretical framework, medical pluralism was developed in the second half of the twentieth century to examine local medical traditions in their diversity, co-existence, and competition, especially with biomedicine. These studies were central to the establishing of the field of medical anthropology. In the context of today’s globalisation, medical pluralism retains its analytical importance, especially in the examination of people’s search for alternative cures locally and transnationally, the growing consumer market of ‘holistic’, ‘traditional’, and ‘natural’ treatments, and the attempts of many countries to incorporate alternative treatments into national healthcare.

While early anthropologists used to focus on local medical traditions in non-Western societies, contemporary scholars examine the place of plural medicine in all societies, including Europe and North America. This shift expanded the scope and terminology with which we describe medical pluralism, for example, by including ‘integrative medicine’ or ‘alternative and complementary medicine’ (or, ‘CAM’). Although there are differences in the usage of these terms, broadly speaking, integrative medicine means that one medical provider offers both biomedicine and nonbiomedical elements as part of a holistic treatment course, while CAM refers to procedures outside biomedicine.

Anthropological studies examine nonbiomedical practices from multiple perspectives, illuminating the role of patients, doctors, markets, and governments in shaping them. As this entry will show, medical pluralism as a concept enables analyses of medicine beyond the dualism of Western/non-Western, modern/traditional, or local/global, by showing how all medical knowledge and practice, be that biomedicine or some regional tradition, is inherently plural, ever-changing, and culturally porous. Such realisation was a result of scholarly debates that problematised the concepts of a medical ‘system’, ‘tradition’, and ‘pluralism’ themselves, as explained in the first section of this entry. The entry then describes the studies of how medical pluralism is influenced and regulated by the state, followed by the studies of medical pluralism in relation to the discourses on modernity, science, and efficacy; gender; and globalisation.[1]

Medical ‘system,’ ‘tradition,’ and ‘pluralism’

Anthropological interest in non-Western medicine dates to the early twentieth century when W.H.R. Rivers (1924) proposed that medicine should be treated as a separate system of knowledge. However, it was only in the 1950s that medical systems began emerging as a focus of anthropological studies. Although the term ‘medical pluralism’ had not yet been introduced, scholars like George Foster (1953) showed the importance of accounting for the impact of colonial and global processes on local medicine, which can result in the eclecticism of medical concepts and therapies as practiced in people’s everyday lives.

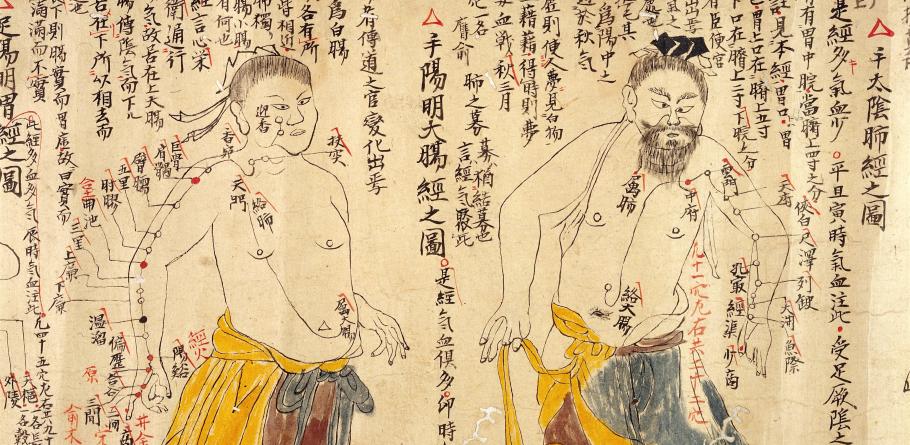

The studies of medical pluralism proper began in the late 1970s–early 1980s, when anthropologists launched a comparative study of Asian medicine, exemplified by an influential volume, Asian medical systems (1976), edited by Charles Leslie. The title and content of this volume, as well as the definition of medical pluralism as ‘differentially designed and conceived medical systems’ in a single society (Janzen 1978: xviii), show that a central concept in these studies was ‘system’ (see also Kleinman 1978; Leslie 1978, 1980; Press 1980). In line with how anthropologists studied kinship systems or religious systems, medical anthropologists sought to understand and classify heterogeneous medical knowledge and practice as holistic ‘systems’. This often entailed the assumption that each medical system is characterised by unique epistemology, disease etiology (origins and causes of diseases), and corresponding diagnostic and healing methods. For example, Unani medicine, which is a Greco-Arabic tradition practised in contemporary South and Central Asia, is a medical system because it has an elaborate understanding of body and bodily processes as affected by four humors (elements) which need to be maintained in certain balance to avoid sickness. If a person falls sick, a trained Unani specialist can employ a variety of techniques to identify the type of abnormality in the balance of humors and prescribe a treatment to restore a healthy humoral state.

In attempts to classify medical systems, scholars used various criteria. Some took a geographical scale to make a distinction between local systems (folk medicine), regional systems (like Unani medicine or traditional Chinese medicine), and cosmopolitan medicine (Dunn 1976). Others used disease etiology, proposing that all medical systems are either ‘personalistic’, when a disease is explained as a result of a purposeful action of a human, god, or other actors, and ‘naturalistic’, when a disease is thought to be caused by non-personal forces such as weather or humors (Foster 1976). Other scholars chose writing as a criterion to distinguish ‘little-tradition medicine’ that did not have written accounts from the ‘great-tradition medicine’ that was based on medical texts (Leslie 1976; Obeyesekere 1976, borrowing from Redfield 1956).

However, the attempt to present medical knowledge as consisting of independent, ‘differentially designed and conceived’ systems was quickly recognised as problematic because it downplayed important mutual developments and influences: for example, so-called folk medicine can borrow ideas and methods from regional medicine like Ayurveda, which itself can be influenced by other regional medicines and cosmopolitan biomedicine. Similar problems arise when medical pluralism is defined through the notion of ‘tradition’, for example, as ‘the coexistence in a single society of divergent medical traditions’ (Durkin-Longley 1984: 867). Without critical reflection, the term ‘tradition’ can inadvertently present medical knowledge and practices as something continuous and unchanged since ancient times. In reality, medical ‘traditions’ are ever-changing and quickly respond to socioeconomic processes, which makes them just as modern as biomedicine. Moreover, the idea of ‘divergent traditions’ can be overly reductionist because it presents medical knowledge and practices as belonging to distinct, separable entities uniform throughout large culture areas, while in fact they are often intertwined, heterogeneous, and varied.

It is therefore not surprising that medical anthropologists have struggled to define medical pluralism itself. How can we write about a plurality of traditions, if traditions are themselves plural? To address this problem, scholars have emphasised that medical ‘systems’ and ‘traditions’ are to be understood as analytical constructs, not as real separable areas of medical knowledge with apparent internal homogeneity and rigid boundaries (Nordstrom 1988; Waxler-Morrison 1988). It has also been argued that the idea of distinct ‘systems’ or ‘traditions’ is divorced from how patients and even doctors themselves understand and use various medicines (Khalikova 2020; Naraindas, Quack & Sax 2014; Mukharji 2016). For example, Marc Nichter documented how healers in South India provided a unique blend of therapies and medicines tailored to patients’ pockets and preferences (Nichter 1980). This phenomenon of mixing and blending different medical approaches is sometimes termed ‘medical syncretism’ (see Baer 2011: 419).

Beside medical syncretism, scholars have experimented with other analytical conceptualisations such as eclecticism and hybridity (Brooks, Cerulli & Sheldon 2020) to highlight how seemingly distinct medical traditions can be practiced in eclectic and entangled ways, where every doctor-patient encounter entails a negotiation of diverse medical ideas and treatments resulting in a unique outcome to the extent of unrecognisable amalgamation. Other scholars prefer the notion of the ‘therapeutic itineraries’, i.e., ‘precise pathways taken by patients’, as well as their reasons for choosing and staying with chosen treatment courses (Orr 2012). Yet other anthropologists use the term ‘medical diversity’ to describe mixtures, borrowings, and intersections of various therapeutic ideas, methods, and attitudes (Krause, Alex & Parkin 2012).

All these examples highlight that the studies of medical pluralism quickly pushed anthropologists to examine how medicine is practiced. Even before postmodern critiques of the notion of culture as a bounded entity, and before the emergence of theoretical frameworks that emphasised practice and agency, some medical anthropologists had already began examining medicine as it unfolds in practice: in doctor-patient relations and patient’s health-seeking strategies. Studies of the ‘hierarchy of medical resort’ (Romanucci-Ross 1969), for example, questioned when and why people choose one therapeutic option over another: Do people ‘shop around’, seeking multiple therapies for a single disease, or do they use different therapies for different kinds of illness? Do patients use various treatments simultaneously or sequentially? As a result of studying such questions, scholars demonstrated the importance of cultural, medical, and socioeconomic factors that lead to various scenarios. People’s choices can depend on a disease type, its folk interpretations, patients’ social status, their worldview, available information, as well as the cost and accessibility of treatment (Gould 1965; Beals 1976).

Another line of studies utilised decision-making models—a term borrowed from cognitive anthropology. These models embody a concern with how people choose a treatment, rather than what they choose and in which order (Garro 1998; Janzen 1978; Young 1981). The emphasis is on cognitive aspects of health-seeking behaviour, conversations about medical options, and the pragmatic aspects of decision-making. For example, people often make medical decisions by consulting their relatives or accepting what is given to them by senior family members: parents choose treatments for children, husbands for wives, and adults for elderly parents. This centrality of kinship in medical pluralism was an important finding of the studies of therapeutic decision-making (Janzen 1978; 1987).

Another milestone in the theorisation of medical pluralism was the recognition that it is present in Western societies too. While traditional medicine was initially mostly studied in non-Western and postcolonial societies in contrast to a single ‘cosmopolitan medicine’, scholars soon demonstrated that even in seemingly homogenous or developed societies like the US, medicine is pluralistic by nature (Leslie & Young 1992; Kleinman 1980). If we look closely at how people deal with illness, alternating between biomedical drugs or home remedies, psychotherapy or religious healing, osteopathy or chiropractic, and other alternatives (Naraindas 2006; Zhang 2007), we can see that medical pluralism is present in every contemporary society. Moreover, biomedicine itself is pluralistic: its practitioners ascribe to various conceptions of health and illness, health care services differ significantly, including across the private and public sectors, and established and experimental biomedical treatments co-exist and compete with one another.

Thus, rather than juxtaposing Western and non-Western therapies (as was done by Rivers in the early twentieth century), medical anthropologists since the 1970–1980s have been interested in both differences as well as similarities between biomedicine and other medical approaches. Medical pluralism thus provided an important framework that broke away from a reductionist dichotomy of biomedicine versus ethnomedicine, or the West versus the rest. From this perspective, biomedicine could be studied as yet another tradition, one of many options that patients around the world use.

However, biomedicine is not a neutral option at par with other medicines. Scholars of medical pluralism have highlighted its hierarchical nature: nonbiomedical traditions often occupy a subordinate position to hegemonic biomedicine in terms of social prestige, education, employment opportunities, and funding (Baer 1989, 2011). For example, biomedical doctors often secure higher salaries and social respect than alternative medical providers (but not always, see Kim 2009). Critical medical anthropologists have argued that the spread of biomedicine across the world is premised on coercive factors, including the colonial past and biomedicine’s alignment with the state power, rather than on ‘natural development’ or medical superiority of biomedicine (Lock & Nguyen 2010; Young 1981).

Nevertheless, contrary to the logic of modernisers who argue for biomedicine’s technological advantage, local therapies did not die out. Why not? Some scholars suggested that this had to do with people’s dissatisfaction with biomedicine and perceptions that traditional medicine is better suited for local illnesses, safer and does not produce side-effects (Farquhar 1994: 19; Lock 1980: 259). Other scholars emphasised the doctors’ perspectives: alternative and biomedical practitioners occupy different medical niches and catered to distinct clientele (Waxler-Morrison 1988; Leslie 1992).

The above-mentioned questions and answers were shaped by the fact that most theoretical work on medical pluralism was based in colonial and postcolonial contexts. Colonialism had a colossal impact on scholars’ interpretations of local medical knowledge and practice. Both in public health policies and writings of early medical anthropologists, a frequently idealised Western medicine was conceived of as a yardstick against which other healing practices should be evaluated. Today, scholars are increasingly critical about the dichotomies of ‘Western’ and ‘Eastern’ medicine, ‘modern’ and ‘traditional’ medicine, or even ‘science’ and ‘belief’. Moreover, contemporary medical anthropologists pay attention to the hierarchies that exist among nonbiomedical systems and within biomedicine itself.

Nevertheless, the residue of such dichotomies can still be found in the academic literature and in public discourse, where the new terms of ‘complementary and alternative medicine’ may unwittingly reinforce the subjugated place of nonbiomedical knowledge and practice. Often the subjugated place results from the lack of legitimation of nonbiomedical therapies by the state. How and why the state regulates medical pluralism is, therefore, another prominent area of scholarly inquiry. Studies that focus on global political economic inequalities often do so to disentangle the multiplicities and hierarchies of medical practice, especially as influenced by state ideologies and transnational markets.

The state

Today, most governments take an active role in regulating medical pluralism: they can either ban alternative medicine as ‘quackery’ and ‘pseudoscience’, provide ways to integrate it partially into biomedical infrastructure, or provide it with full support as a standalone institution (Adams & Li 2008; Berger 2013; Kloos 2013; Lock 1990; Scheid 2002). How do governments make such decisions? Why are some medical traditions denied legitimation while others are promoted? What is at stake when a nonbiomedical tradition is officially recognised? What kind of transformations occur in its ontology and epistemology after its legitimation and institutionalisation? What are the implications for practitioners, patients, and society in general? These are some central questions raised in the studies that investigate the relations between medical pluralism and the state.

A government’s support for nonbiomedical treatments can be a strategic move to conform to international directives, especially after the 1970–1980s, when the World Health Organization (WHO) promoted the integration of traditional therapies as ‘a means of accessing gaps in service provision’ (Hampshire & Owusu 2013: 247-8). ‘Filling the gap’ is a common trope in official rhetoric in countries with large rural populations where biomedical services and institutions are limited. Here a standardised, regulated alternative medicine is presented as a necessary means to achieve a common good. However, more critically, the recognition of alternative medicine can also be seen as the government’s failure to provide accessible and affordable biomedical care, pushing people to rely on services of ‘a large, unregulated, unqualified medical cadre of practitioners’, as argued by some scholars in the case of India (Sheehan 2009: 138). Similarly, in post-Soviet Cuba, the government partially incorporated traditional herbal medicine into the healthcare system as a strategy to disguise massive shortages in biomedical pharmaceuticals after the decline in supply from countries of the socialist block (Brotherton 2012: 46).

In multicultural contexts, the legitimation of alternative medicine can be also taken as the government’s responsibility to satisfy popular demand. Often associated with migrant populations, plural and ‘culturally sensitive medicine’ is at times demanded as citizens’ rights. Some scholars have pointed out the importance of providing non-discriminatory medical services to migrants, especially to those who may not share a biomedical model of health and disease (Chavez 2003). Others go as far as to argue that integrating nonbiomedical healing should be a goal for modern democratic governments as that would recognize the rights and identities of minority groups. For example, the official healthcare system in Israel includes many alternative medical modalities, but not Arab herbal medicine, indicating that the cultural preferences of the Arab minority may remain undermined (Keshet & Popper-Giveon 2013).

An important insight from the literature on the state shows that governments are selective about the degree of legitimacy and support they provide to medical traditions. Thus, medical pluralism can become a mechanism for and the end product of carefully planned and instituted government efforts for managing population and economy. For example, by analysing the New Order government of Indonesia under President Suharto, Steve Ferzacca (2002) proposes to understand medical pluralism as a form of state rule. Ferzacca demonstrates how the Indonesian government manipulated the plurality of medical practices by recognising and promoting only those that fit into the overarching ideology of ‘development’.

Another example of selective legitimation of nonbiomedical knowledge and practice is demonstrated by Helen Lambert (2012). She highlights how medical pluralism is characterised by the ‘hierarchies of legitimacy’ when the government grants support to Ayurveda, Yoga and other text-based medical systems, while the practitioners of local traditions, like bonesetters in India, remain at the ‘margins of government legitimation’, even though they are seen as experts in their local communities.

This is important, because to nonbiomedical doctors, official recognition brings visibility, further societal acceptance, and legal employment (Blaikie 2016). Once a medical tradition is granted official status, its practitioners can demand higher salaries, better facilities, funding, and more opportunities. In contrast, healers who are left outside government legitimation face the danger of losing community respect, losing clientele, and gradually disappearing (Hampshire & Owusu 2013; Kleinman 1980). At the same time, Linda Connor (2004) argues that state legitimation does not necessarily affect people’s medical preferences: in an ethnographic study of residents of Australian suburbs, she demonstrates that people often choose nonbiomedical treatments outside the official healthcare settings for their perceived effectiveness and imagined ‘natural’ qualities in contrast to pharmaceutical drugs.

A related outcome of the professionalisation of traditional medicine is the marginalisation of women’s knowledge. In Ghana, Kate Hampshire and Samuel Owusu (2013) have observed that the government’s efforts to ‘professionalise’ traditional healing have led to the dominance of male practitioners who had means and connections to become ‘professional’ doctors. In contrast, women lacked those means, which created a context for a potential loss of their traditional knowledge, particularly concerning children’s illness.

However, even officially sanctioned and integrated medical traditions face many challenges, including the problem of ‘translation’, when the state, biomedical healthcare, or the market appropriate local medical knowledge by ignoring, undermining, or transforming its value system (Bode 2008; Cho 2000; Craig 2012; Janes 1995; Saks 2008). For example, due to ideological pressures from the Chinese government, certain procedures of Tibetan medicine have been pushed to the periphery of practice as being ‘religious’ and ‘unscientific’ (Adams, Schrempf & Craig 2010). In a similar way, in India, bhūtavidyā — one of the eight branches of Ayurveda, which deals with non-human entities — has been discounted by many contemporary Ayurvedic patients and doctors (Naraindas 2014: 112-3; Hardiman 2009).

Even if institutionalisation does not result in a distortion of meaning and repertoire of traditional medicine, it nevertheless transforms flexible healing practices into coherent units of standardised therapies, imposing therapeutic normativity and orthopraxy. This means that only select medical texts, ideas, and procedures along with their ‘correct’ interpretations get to be included in medical education and training; doctors must follow these normative ways of doing medicine if they wish to remain in institutional settings. For example, the institutionalisation of traditional Chinese medicine in the 1950s was accompanied by measures to ‘define, delimit, name, and “purify”’ select practices to comply with the communist ideology (Farquhar 1994: 14-5). Also, the professionalisation of traditional medicine affects how medical knowledge is transmitted and learned. While traditional medical knowledge is often passed through apprenticeship from a teacher to one or several students, state involvement often brings the introduction of a college system, which may break a vertical structure of teacher-student and elder-younger relations (Farquhar 1994: 15; Smith & Wujastyk 2008: 7).

As various political and social actors have high stakes in promoting a particular medical ideology, medical anthropologists have been careful to show the existence of heterogeneous powers within governments as well as rival groups of citizens, their competing claims about medical traditions, and various ideological positions embedded in those claims (Khan 2006). For example, because of the co-constituted relations between Western imperialism and biomedicine, the ‘revival’ of ‘indigenous’ medical systems is often embedded in anti-colonialist and nationalist discourses (Langford 2002). In other words, postcolonial states articulate their aim to recuperate local medicine as a sign of liberation from structures of colonial rule. This goal becomes particularly complex in the countries with more than one nonbiomedical system, through which nationalist ideologies can be activated (Alter 2015; Khalikova 2018).

Modernity, science, and efficacy

Discourses on nationalism and national medicine are often interlaced with debates about modernity (Croizier 1968; Khan 2006). An important insight from this literature is the problematisation of the terms ‘traditional’ and ‘modern’. While twentieth century anthropologists tended not to look at nonbiomedical practice as already modern, by the end of the century, scholars began exploring ways in which the modern and the traditional were co-constructed and fluid.

Based on her research on three medical traditions in Bolivia—cosmopolitan medicine, indigenous Aymara medicine, and home remedies—Libbet Crandon-Malamud (1991) introduced the notion of 'medical ideologies' to show that when people say something about their illness, they are also saying something about themselves and making statements about political and economic realities (1986: 463; 1991: ix, 31). Consequently, people’s beliefs and debates about therapeutic authenticity, efficacy, and legitimacy of a medical tradition can explain a lot about a society in a local and global context.

In many parts of the world—but especially in postcolonial countries struggling with the cultural and political legacies of colonialism—doctors and patients attempt to reconfigure traditional medicine through the notions of modernity, science, and technological progress. Medical practitioners often employ ideologies of both modernity and tradition, in response to demands and expectations from patients, government policies, and other actors. The same holds true for the notion of science. For example, Vincanne Adams has documented how practitioners of Tibetan medicine in China have to use the language of science in order to conform to the science-oriented ideologies of the communist state, while maintaining that Tibetan medicine is efficacious and scientific in its ‘own’ way (i.e., not measurable by biomedical standards). Thereby, they satisfy the aspirations of the local population for culturally appropriate therapy and demands of the international market for a ‘unique’ Tibetan medicine (2002b: 213).

But why do patients seek alternative medicine? Does it work? The problem of efficacy has been important in the study of medical pluralism since its conception (Leslie 1980), but anthropologists still lack a consensus about what ‘efficacy’ means and how it should be analysed (Waldram 2000). If we take efficacy to be a statistically measurable capacity of a drug to produce a desired relief, then in general scholars of medical pluralism tend to avoid making claims about whether or not alternative treatments are efficacious (Ecks 2013: 12; Langford 2002: 200). Instead, scholars have been more interested in understanding the ‘perceived’ efficacy by bringing attention to the feelings, subjective experiences, and views of patients and doctors as they rationalise their use of alternative medicine (Poltorak 2013).

Patients often ‘shop around’, alternating between therapeutic options, until they find what works for them. Here, the concern may be not about whether alternative medicine brings measurable therapeutic relief or not, but what kind of effects it produces. For example, in India many people insist that nonbiomedical treatments such as Ayurveda and homeopathy work but do so gradually and therefore are mild on the body, while biomedicine provides immediate relief but has numerous side-effects (Langford 2002). In other words, both alternative medicine and biomedicine can be seen as efficacious, but in different ways. In North America, patients who are dissatisfied with biomedicine turn to alternative medicine because it is seen as instilling a sense of ‘safety, comfort and well-being’ by appealing to nature, wholeness, and harmony, providing treatments in pleasant surroundings, whereas biomedicine is criticised ‘for its failure to engage the personal and cultural dimensions of suffering’, and for involving ‘painful, disorienting, and disturbing treatments aimed not at comfort but biological efficacy’ (Kirmayer 2014, 38-9). Such juxtaposition of alternative medicine as warm and personal, while biomedicine may be cold and institutional, frames many cultural discourses about how and why different treatments work.

Probing the questions of efficacy of alternative medicine even further, Sienna Craig argues that the very question ‘Does a medicine work?’ is a fabrication of a hegemonic, clinical perspective; instead, one needs to ask, ‘What makes a medicine “work”? How are such assertions made, by whom, and to what ends?’ (2012: 4). Craig argues that the question of efficacy serves as a mechanism for ‘translating’ nonbiomedical knowledge into the language of biomedicine and science, which is itself an outcome of global governance of medicine (such as by the WHO) and neoliberalism. In other words, scholars highlight that the efficacy of biomedicine is embedded in its social and economic power. This means that efficacy is not a neutral objective category, but something that needs to be interrogated with regard to what counts as evidence and who gets to define it.

As reminded by Margaret Lock and Mark Nichter, social claims of efficacy can have actual impact on patient’s health, since the ‘attributions of efficacy, however determined, and be they positive or negative, influence treatment expectations and thus effectiveness in their own right’ (2002: 21). Therefore, anthropological studies often explore various truth claims, the semantics and language of efficacy: how efficacy is spoken about in local terms, how it is invoked by patients and doctors themselves, and how various ideas about efficacy can influence the health outcomes. This includes negative health outcomes too, when claims of the efficacy of alternative treatments can create an atmosphere of distrust towards established biomedical treatments (such as vaccines). Hence, it is important to recognise that the existence of plural medical options can cause confusion and be detrimental to people’s health: while shopping around for a therapy that appears right to them, patients may delay using medicines with proven effects.

Gender

For most of the twentieth century, the studies of medical pluralism contained only scattered references to women—for example, as primary users of alternative medicine or as traditional healers. Today, there is a growing body of literature that critically addresses gender and gender ideologies in the context of medical pluralism (Cameron 2010; Fjeld & Hofer 2011; Flesch 2010; Menjívar 2002; Schrempf 2011; Selby 2005; Zhang 2007). A related area of scholarship is focused on reproduction, traditional birth attendants, and the issues of gender equity in pluralistic medical settings, particularly within the institutions of intercultural medicine in Latin America.

Many medical traditions such as Tibetan medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, Ayurveda, Unani, and biomedicine used to be the spheres where female doctors, teachers, and authors of medical texts were absent or rare (but see Fjeld & Hofer 2011). In the twenty-first century the situation has started to change, and more women have become practitioners of these previously male-dominated medical traditions. Yet this can also create new inequalities. For example, by examining an increase in female practitioners of Ayurveda in Nepal, Mary Cameron (2010) argues that the ‘feminization of Ayurveda’ has been entangled with the official marginalisation of Ayurveda in the context of biomedicine-dominated healthcare system. In other words, a positive change, such as the increased acceptance of women as alternative practitioners, is negated by the loss of prestige of Ayurveda in Nepal (although this is not the case in India). Another problem is that the increase of female practitioners in alternative medicine can reinforce the stereotypes of women’s ‘innate’ ability to heal and their proximity to nature, as documented in Hannah Flesch’s work (2010) on female students studying Acupuncture and Oriental Medicine in the US. Thus, these studies illuminate that the discourses on alternative/traditional medicine are often gendered.

Other scholars have shown how nonbiomedical health-related practices can be linked to ideas of masculinity and socio-political ideologies. By examining traditional male wrestlers in India, Joseph Alter (1992) has discovered that their practices of celibacy, self-control, and dietary regimens are linked to their unique interpretations of modernity, masculinity, and nationhood. While many Indian citizens conceive of biomedicine as a link to modernity and good health, traditional wrestlers engage with nonbiomedical practices to strengthen a national physique and achieve culturally appropriate masculinity by countering the harmful impact of Western consumerism and sexual liberation.

Globalisation

The studies of medical pluralism and globalisation emerged in the early 2000s in an attempt to make sense of medical practices in the face of transnational migration, medical tourism, the global flow of alternative pharmaceuticals, the spread of the Internet, and other processes that have problematised national and cultural boundaries, creating avenues for the global exchange of local and ‘new age’ medical knowledge (Lock & Nichter 2002; Krause 2008; Wujastyk & Smith 2008; Hampshire & Owusu 2012). Certainly, transcultural connections were forged intensively during the colonial era and even earlier; however, the close interconnectedness of the world is a relatively recent phenomenon, which both allows and compels people to render their therapeutic itineraries ever more diverse and geographically dispersed. This complexity has compelled scholars to rethink the concept of medical pluralism as no longer confined to a single society but as spanning national borders (Raffaetà et al. 2017). Rather than being limited by medical options within a certain locality, contemporary health-seekers can avail of pluralistic medical approaches, experts, and institutions by crossing borders physically and virtually.

On the one hand, nonbiomedical practices are taken outside their place of origin, as exemplified by the popularity of German anthroposophic medicine in Brazil, the proliferation of Yoga centres outside India, or the spread of acupuncture outside East Asia (Alter 2005; Kim 2009; Wujastyk & Smith 2008). Unlike many twentieth century studies of the influences between the ‘core’ and the ‘periphery’ (as per World Systems Theory), contemporary scholars explore South-South and other global connections: for example, the incorporation of traditional Chinese medicine into pluralistic medicine in Tanzania (Hsu 2002; Langwick 2010). Additionally, there is an emerging literature on the impact of new communication technologies on plural medicine (Hampshire & Owusu 2012; Krause 2008). Such research addresses ‘telemedicine’, self-help Internet blogs, email consultations with overseas nonbiomedical doctors, and other technologies (for example, digital apps on meditation and Yoga) that have significantly shaped the ways in which medical pluralism is conceived and practiced.

At the same time, patients themselves travel around the world in the search of nonbiomedical treatments. Here, some scholars distinguish medical tourism, associated with biomedical treatment, from health tourism or wellness tourism associated with traditional and alternative medicine (Reddy & Qadeer 2010: 69; also Smith & Wujastyk 2008: 2-3). For example, health-seeking tourists may travel to India in pursuit of ‘authentic’ Ayurvedic therapy, Yoga, or spiritual healing (Langford 2002; Spitzer 2009).

Therapeutic trajectories of migrants in host countries is also a particularly fast-growing area of research, especially because migrants carry different medical ideologies and attitudes that might raise concerns in the sphere of public health, health policy, and public discourses (Andrews et al. 2013; Cant & Sharma 1999; Chavez 2003; Green et al. 2006; Krause 2008). Some of these studies examine how minority groups seek satisfactory treatment in biomedicine-dominated contexts. For example, Tracy Andrews and others (2013) examine how adult Hispanic migrants in the US make therapeutic decisions for their children in a pluralistic health care setting that includes both biomedical providers and famous Mexican healers in the vicinity. Many studies emphasise that migrants resort to alternative practitioners, particularly from their community, because of language difficulties, cultural preferences, a search for a specific herbal or spiritual treatment, or fear of being looked down on by biomedical practitioners (Green et al. 2006, Andrew et al. 2013; Lock 1980: 260; Chavez 2003: 201, 219). These challenges can motivate migrants to postpone immediate care and instead make trips to their countries of origin to receive medical treatment. Therefore, medical anthropologists often point out the importance of providing non-discriminatory medical services to migrants, especially to those who may not share a biomedical model of health and disease, and advocate for health policies of ‘integrative’ and ‘culturally-sensitive’ health care (Green et al. 2006; Chavez 2003).

In addition to the focus on patients, scholars of globalised healthcare also investigate the transnational mobilities of medical practitioners and material objects. ‘Traditional’ medicines, healing crystals, talismans, and other paraphernalia, which are not exchanged through formal channels of commerce, often follow along the lines of an informal economy of transnational connections (Hampshire & Owusu 2012; Krause 2008; Menjívar 2002). Kristine Krause (2008) provides an example of ‘transnational therapy networks’ that connect Ghanaian migrants in London, their relatives and friends in other European counties, and traditional healers in Ghana who may ‘directly deliver their products’ to owners of Afro-shops in the UK. In these transnational channels, money, drugs, and prayers are sent between members of the African diaspora in Europe and their friends and suppliers in the countries of origin.

Inspired by the work of Arjun Appadurai (1988) and other scholars of materiality, medical anthropologists have expanded their inquiries of medicine as knowledge and practice to the examination of physicality and the ‘agentive properties’ of medical objects: pills, intake forms, ultrasound prints, medical charts, stethoscopes, syringes, and other equipment are not passive objects but active agents in clinical interactions, as they can influence people’s behaviour, compel action, communicate, instil fear or trust, and even heal. For example, contemporary alternative doctors frequently adopt material objects from other medical traditions, especially from biomedicine: in India, some patients who visit an Ayurvedic doctor demand to be examined by a stethoscope, believing that a touch of a stethoscope has a curative outcome (Nichter 1980). Thus, a stethoscope is not a silent object in a doctor’s room but an agent that speaks, calls for action, and brings confidence.

Such studies of materiality provide the crucial insight that medical pluralism is often unmarked: sometimes neither doctors nor patients see their encounters as pluralistic. As shown in Stacey Langwick’s work in Tanzania, a ‘traditional’ healer may routinely use a syringe and ask to bring an X-ray from biomedical hospitals. The presence of ‘modern’ medical technologies can ‘challenge the self-evidence of boundaries between traditional and modern medicine’ (2008: 429).

Unlike the above research on unauthorised, informal transnational flows of medicines, there is a new scholarship on the commercial flow of ‘alternative’ pharmaceuticals and the operations of alternative industries beyond national borders. Building on previous studies of marketisation of alternative medicine in domestic contexts (Adams 2002a; Banerjee 2009; Bode 2008; Craig 2011, 2012; Kim 2009), this scholarship highlights the transformations under the pressures of a global neoliberal economy, when many nonbiomedical practices can no longer be dismissed as local, marginal, or alternative traditions. It makes the case for recognising them as transnational, mainstream, innovative, and profit-driven industries (Kloos 2017; Kloos et al. 2020; Pordié & Gaudillière 2014; Pordié & Hardon 2015).

Conclusion

Developed in the 1970s–1980s, the concept of medical pluralism offered novel ways of understanding diverse medical practices and their relations with biomedicine. It went beyond the early twentieth century descriptions of indigenous healing beliefs and was a crucial concept for establishing the field of medical anthropology. By attempting to overcome the dualistic representation of Western/modern and non-Western/traditional medicine, scholars of medical pluralism demonstrated that the diversity of medical ideas, approaches, experts, and institutions exists in every complex society, even in the West. Rather than merely focusing on health and healing, medical pluralism highlights the heterogeneity, multiplicity, and competition that permeate medical thought and practice. Although many scholars have challenged the notion of ‘pluralism’ and suggested replacing it with other terms such as eclecticism or diversity, medical pluralism remains a valuable framework.

Many anthropologists have come to criticise the ideas of medical ‘systems’ and medical ‘traditions’ as being overly rigid, even essentialising. Instead, they moved towards the exploration of doctor-patient negotiations, paying attention to whether different actors see therapies as pluralistic, what therapeutic plurality means, who benefits from their promotion, and what kind of inequalities exist between various categories of medicine. Most prominent examples of such inequalities include the hegemonic position of biomedicine supported by science discourses due to which nonbiomedical knowledge and practices are dubbed ‘alternative’ and ‘complementary’, if not entirely fake.

However, the studies of medical pluralism also show that, paradoxically, traditional and alternative medical practices did not disappear under the dominance of biomedicine. Although sometimes lacking official support, they are widely sought out around the world not only by rural populations but also by consumers with wealth and power. The analyses of pluralism as resulting from medical tourism, the spread of the Internet, and the pharmaceuticalisation of indigenous therapies have become important areas of study. This scholarship acknowledges that multiple actors such as medical providers, tourists and migrants, corporations, national leaders, and other categories of citizens—all have their own stake in various medical traditions. Therefore, instead of a narrow focus on colonial and postcolonial situations, researchers explore ‘new’ (Cant & Sharma 1999) and ‘transnational’ (Raffaetà et al. 2017) forms of medical pluralism. The pressing need to account for local and global media, migration, and the rapid growth of medical and other technologies have also forced scholars to change their methods. They moved from studying health practices in a single community to ‘following’ people, objects, and ideas across borders (as per Marcus 1995), showing that people’s therapeutic options have become truly transnational and even more pluralistic. The intensified pluralism is also visible if we account for the ‘virtual’ field in which both biomedicine and nonbiomedical healing is increasingly offered. As a result, scholars have also moved from the descriptions of nonbiomedical practices as small, local, low-cost, marginal alternative traditions to recognising them as large, profit-driven, and mainstream ‘industries’ that occupy substantial market segments domestically, while also rapidly expanding globally. All of this demonstrates that medical pluralism does not just remain an important feature of modern life, but that it is constantly changing in form and content.

References

Adams, V. 2002a. Randomized controlled crime: postcolonial sciences in alternative medicine research. Social Studies of Science 32, 659-90.

——— 2002b. Establishing proof: translating ‘science’ and the state in Tibetan medicine. In New horizons in medical anthropology: essays in honour of Charles Leslie (eds) M. Nichter & M. Lock, 200-20. New York: Routledge.

Adams, V. & F.F. Li 2008. Integration or erasure? Modernizing medicine at Lhasa's Mentsikhang. In Exploring Tibetan medicine in contemporary context: perspectives in social sciences (ed.) L. Pordie, 105-31. London: Routledge.

Adams, V., M. Schrempf & S. Craig (eds) 2010. Medicine between science and religion: explorations on Tibetan grounds. New York: Berghahn Books.

Alter, J. 1992. The wrestler’s body: identity and ideology in North India: Berkeley: University of California Press.

——— (ed.) 2005. Asian medicine and globalization. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

——— 2015. Nature cure and Ayurveda: nationalism, viscerality, and bio-ecology in India. Body and Society 21(1), 3-28.

Andrews, T.J., V. Ybarra & L.L. Matthews 2013. For the sake of our children: Hispanic immigrant and migrant families’ use of folk healing and biomedicine. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 27, 385-413.

Appadurai, A. 1988. The social life of things: commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge: University Press.

Baer, H. 1989. The American dominative medical system as a reflection of social relations in the larger society. Social Science and Medicine 28, 1103–12.

——— 2011. Pluralism: an evolving and contested concept in medical anthropology. In A companion to medical anthropology (eds) M. Singer & P. Erickson, 405-24. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Banerjee, M. 2009. Power, knowledge, medicine: Ayurvedic pharmaceuticals at home and in the world. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Beals, A. 1976. Strategies of resort to curers in South India. In Asian medical systems: a comparative study (ed.) C. Leslie, 184-200. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Blaikie, C. 2016. Positioning Sowa Rigpa in India: coalition and antagonism in the quest for recognition. Medicine, Anthropology, Theory 3, 50-86.

Bode, M. 2008. Taking traditional knowledge to the market: the modern image of the Ayurvedic and Unani industry, 1980-2000. New Delhi: Orient Blackswan.

Brooks, L.A., A. Cerulli & V. Sheldon 2020. Introduction. Asian Medicine 15(1), 3-9.

Brotherton, S. 2012. Revolutionary medicine: health and the body in post-Soviet Cuba. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Cameron, M. 2010. Feminization and marginalization? Medical Anthropology Quarterly 24, 42-63.

Cant, S. & U. Sharma 1999. A new medical pluralism? Complementary medicine, doctors, patients, and the state. London: UCL Press.

Chavez, L. 2003. Immigration and medical anthropology. In American arrivals: anthropology engages the new immigration (ed.) N. Foner, 197-227. Santa Fe: School of American Research Press.

Cho, H.-J. 2000. Traditional medicine, professional monopoly and structural interests: a Korean case. Social Science and Medicine 50, 123-35.

Connor, L. 2004. Relief, risk and renewal: mixed therapy regimens in an Australian suburb. Social Science and Medicine 59, 1695-705.

Craig, S. 2011. “Good” manufacturing by whose standards? Remaking concepts of quality, safety, and value in the production of Tibetan medicines. Anthropological Quarterly 84, 331-78.

——— 2012. Healing elements: efficacy and the social ecologies of Tibetan medicine. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Crandon-Malamud, L. 1991. From the fat of our souls: social change, political process, and medical pluralism in Bolivia. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Croizier, R. 1968. Traditional medicine in modern China: science, nationalism, and the tensions of cultural change. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Dunn, F. 1976. Traditional Asian medicine and cosmopolitan medicine as adaptive systems. In Asian medical systems: a comparative study (ed.) C. Leslie, 133-58. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Durkin-Longley, M. 1984. Multiple therapeutic use in urban Nepal. Social Science & Medicine 19, 867-72.

Ernst, W. (ed.) 2002. Plural medicine, tradition and modernity: historical and contemporary perspectives: views from below and from above, 1800-2000. New York: Routledge.

Farquhar, J. 1994. Knowing practice: the clinical encounter of Chinese medicine. Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press.

Ferzacca, S. 2002. Governing bodies in New Order Indonesia. In New horizons in medical anthropology: essays in honour of Charles Leslie (eds.) M. Nichter & M. Lock, 35-57. New York: Routledge.

Fjeld, H. & T. Hofer 2011. Women and gender in Tibetan medicine. Asian Medicine 6(2) Special Issue: Women and Gender in Tibetan Medicine (eds) H. Fjeld & T. Hofer, 175-216.

Flesch, H. 2010. Balancing act: women and the study of complementary and alternative medicine. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice 16, 20-5.

Foster, G. 1953. Relationships between Spanish and Spanish-American folk medicine. The Journal of American Folklore 66, 201-17.

——— 1976. Disease etiologies in non‐Western medical systems. American Anthropologist 78, 773-82.

Garro, L. 1998. On the rationality of decision-making studies: part 1: decision models of treatment choice. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 12, 319-40.

Gould, H. 1965. Modern medicine and folk cognition in rural India. Human Organization 24, 201-8.

Green, G. et al. 2006. ‘We are not completely westernised’: dual medical systems and pathways to health care among Chinese migrant women in England. Social Science and Medicine 62, 1498–509.

Hampshire, K. & S. Owusu 2012. Grandfathers, Google, and dreams: medical pluralism, globalization, and new healing encounters in Ghana. Medical Anthropology 32, 247-65.

Janes, C. 1995. The transformations of Tibetan medicine. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 9, 6-39.

Janzen, J. 1978. The quest for therapy: medical pluralism in Lower Zaire. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——— 1987. Therapy management: concept, reality, process. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 1, 68-84.

Keshet, Y. & A. Popper-Giveon 2013. Integrative health care in Israel and traditional Arab herbal medicine: when health care interfaces with culture and politics. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 27, 368-84.

Khalikova, V. 2018. Medicine and the cultural politics of national belonging in contemporary India: medical plurality or Ayurvedic hegemony? Asian Medicine 13, 198-221.

——— 2020. Doctors of plural medicine, knowledge transmission, and family space in India. Medical Anthropology 39(3), 282-96 (available on-line: https://www.doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2019.1656621).

Khan, S. 2006. Systems of medicine and nationalist discourse in India: towards ‘new horizons’ in medical anthropology and history. Social Science and Medicine 62, 2786-97.

Kim, J. 2009. Transcultural medicine: a multi-sited ethnography on the scientific-industrial networking of Korean medicine. Medical Anthropology 28, 31-64.

Kleinman, A. 1978. Concepts and a model for the comparison of medical systems as cultural systems. Social Science and Medicine 12, 85-93.

——— 1980. Patients and healers in the context of culture. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Kloos, S. 2013. How Tibetan medicine in exile became a 'medical system.' East Asian Science, Technology and Society 7, 381-95.

——— 2017. The pharmaceutical assemblage: rethinking Sowa Rigpa and the herbal pharmaceutical industry in Asia. Current Anthropology 58, 693-717.

Kloos, S., H. Madhavan, T. Tidwell, C. Blaikie & M. Cuomu 2020. The transnational Sowa Rigpa industry in Asia: new perspectives on an emerging economy. Social Science & Medicine 245, 1-12.

Krause, K. 2008. Transnational therapy networks among Ghanaians in London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 34, 235-51.

Krause, K. G. Alex & D. Parkin 2012. Medical knowledge, therapeutic practice and processes of diversification. MMG Working Paper 12-11. Gottingen: Max Planck Institute for the Study of Religious and Ethnic Diversity.

Lambert, H. 2012. Medical pluralism and medical marginality: bone doctors and the selective legitimation of therapeutic expertise in India. Social Science and Medicine 74, 1029-36.

Langford, J. 2002. Fluent bodies: Ayurvedic remedies for postcolonial imbalance. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Langwick, S. 2008. Articulate(d) bodies: traditional medicine in a tanzanian hospital. American Ethnologist 35, 428-39.

Leslie, C. (ed.) 1976. Asian medical systems: a comparative study. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——— 1978. Theoretical foundations for the comparative study of medical systems. Social Science and Medicine 12, 65-7.

——— 1980. Medical pluralism in world perspective. Social Science and Medicine 14, 191-5.

——— 1992. Interpretations of illness: syncretism in modern Ayurveda. In Paths to Asian medical knowledge (eds) C. Leslie & A. Young, 177-208. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Leslie, C. & A. Young (eds) 1992. Paths to Asian medical knowledge. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lock, M. 1980. East Asian medicine in urban Japan: varieties of medical experience. Berkeley: University of California Press.

——— 1990. Rationalization of Japanese herbal medication: the hegemony of orchestrated pluralism. Human Organization 49, 41-7.

——— & V.-K. Nguyen 2010. An anthropology of biomedicine. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell.

——— & M. Nichter 2002. Introduction: from documenting medical pluralism to critical interpretations of globalized health knowledge, policies, and practicies. In New horizons in medical anthropology: essays in honour of Charles Leslie (eds) M. Nichter & M. Lock, 1-34. New York: Routledge.

Marcus, G. 1995. Ethnography in/of the world system: the emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology 24, 95-117.

Menjívar, C. 2002. The ties that heal: Guatemalan immigrant women’s networks and medical treatment. International Migration Review 36, 437-66.

Naraindas, H. 2006. Of spineless babies and folic acid: evidence and efficacy in biomedicine and ayurvedic medicine. Social Science and Medicine 62, 2658-69.

———, J. Quack & W. Sax (eds) 2014. Asymmetrical conversations: contestations, circumventions, and the blurring of therapeutic boundaries. New York: Berghahn Books.

Nichter, M. 1980. The layperson’s perception of medicine as perspective into the utilization of multiple therapy systems in the Indian context. Social Science and Medicine 14, 225-33.

Nordstrom, C. 1988. Exploring pluralism: the many faces of Ayurveda. Social Science and Medicine 27, 479-89.

Obeyesekere, G. 1976. The impact of Ayurvedic ideas on the culture and the individual in Sri Lanka. In Asian medical systems: a comparative study (ed.) C. Leslie, 201-17. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Orr, D. 2012. Patterns of persistence amidst medical pluralism: pathways toward cure in the southern Peruvian Andes. Medical Anthropology 31, 514-30.

Pordié, L & J.P. Gaudillière 2014. Introduction: industrial Ayurveda: drug discovery, reformulation, and the market. Asian Medicine 9(1-2), 1-11.

Pordié, L. & A. Hardon 2015. Drugs’ stories and itineraries. On the making of Asian industrial medicines. Anthropology & Medicine 22(1), 1-6.

Press, I. 1980. Problems in the definition and classification of medical systems. Social Science and Medicine 14, 45-57.

Raffaetà, R., K. Krause, G. Zanini & G. Alex 2017. Medical pluralism reloaded. L'Uomo Società Tradizione Sviluppo 1, 95-124.

Reddy, S. & I. Qadeer 2010. Medical tourism in India: progress or predicament? Economic and Political Weekly 14, 69-75.

Redfield, R. 1956. Peasant society and culture. Chicago: University Press.

Rivers, W.H.R. 1924. Medicine, magic, and religion: the Fitz Patrick lectures delivered before the Royal College of Physicians of London 1915 and 1916 (preface by G.E. Smith). London: Kegan Paul and Co.

Romanucci-Ross, L. 1969. The hierarchy of resort in curative practices: the Admiralty Islands, Melanesia. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 10, 201-9.

Saks, M. 2008. Plural medicine and East-West dialogue. In Modern and global Ayurveda: pluralism and paradigms (eds) D. Wujastyk & F. Smith, 29-41. New York: State University Press.

Scheid, V. 2002. Chinese medicine in contemporary China. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Schrempf, M. 2011. Re-production at stake: experiences of family planning and fertility among Amdo Tibetan women. Asian Medicine Special Issue: 6, 321-47.

Selby, M.A. 2005. Sanskrit gynecologies in postmodernity: the commoditization of Indian Medicine in alternative medical and new-age discourses on women’s health. In Asian medicine and globalization (ed.) J. Alter, 120-31. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sheehan, H. 2009. Medical pluralism in India: patient choice or no other options? Indian Journal of Medical Ethics 6, 138-41.

Smith, F. & D. Wujastyk 2008. Introduction. In Modern and global Ayurveda: pluralism and paradigms (eds) D. Wujastyk & F. Smith, 1-28. New York: State University Press.

Spitzer, D. 2009. Ayurvedic tourism in Kerala: local identities and global markets. In Asia on tour: exploring the rise of Asian tourism (eds) T. Winter, P. Teo & T.C. Chang, 138-50. Avingdon: Routledge.

Waldram, J.B. 2000. The efficacy of traditional medicine: current theoretical and methodological issues. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 14(4), 603-25.

Waxler-Morrison, N. 1988. Plural medicine in Sri Lanka: do Ayurvedic and Western medical practices differ? Social Science and Medicine 27, 531-44.

Wujastyk, D. & F. Smith (eds) 2008. Modern and global Ayurveda: pluralism and paradigms. New York: State University Press.

Young, J.C. 1981. Medical choice in a Mexican village. Rutgers: State University of New Jersey Press.

Zhang, E.Y. 2007. Switching between traditional Chinese medicine and Viagra: cosmpolitanism and medical pluralism today. Medical Anthropology 26, 53-96.

Note on contributor

Venera R. Khalikova is a cultural anthropologist and Lecturer at the Chinese University of Hong Kong. She received her PhD from the University of Pittsburgh. Her previous work on medical pluralism and the politics of Ayurveda in North India have appeared in Medical Anthropology, Asian Medicine, and Food, Culture, and Society. Her current interests include the study of migration, race, and gender among Indians in Hong Kong.

Dr Venera R. Khalikova, Department of Anthropology, Chinese University of Hong Kong, NAH 322, Shatin, N.T., Hong Kong. venera.khalikova@cuhk.edu.hk

[1] For additional reviews of this concept in anthropology as well as sociology and history, readers can consult texts by Hans Baer (2011); Sarah Cant & Ursula Sharma (1999), Waltraud Ernst (2002), and Roberta Raffaetà et al. (2017).